The Allies

As Collinsport prepares to conclude yet another profitable tourist season – despite a series of gruesome, unsolved murders, of tourists no less – there are those who have very little regard to the fortunate prosperity. They have far more sinister matters to consider. And so on the foreboding and long abandoned island of St. Eustace, old allies gather, for they are well aware that a storm has been brewing – a storm which will bring severe consequences for the living and the undead.

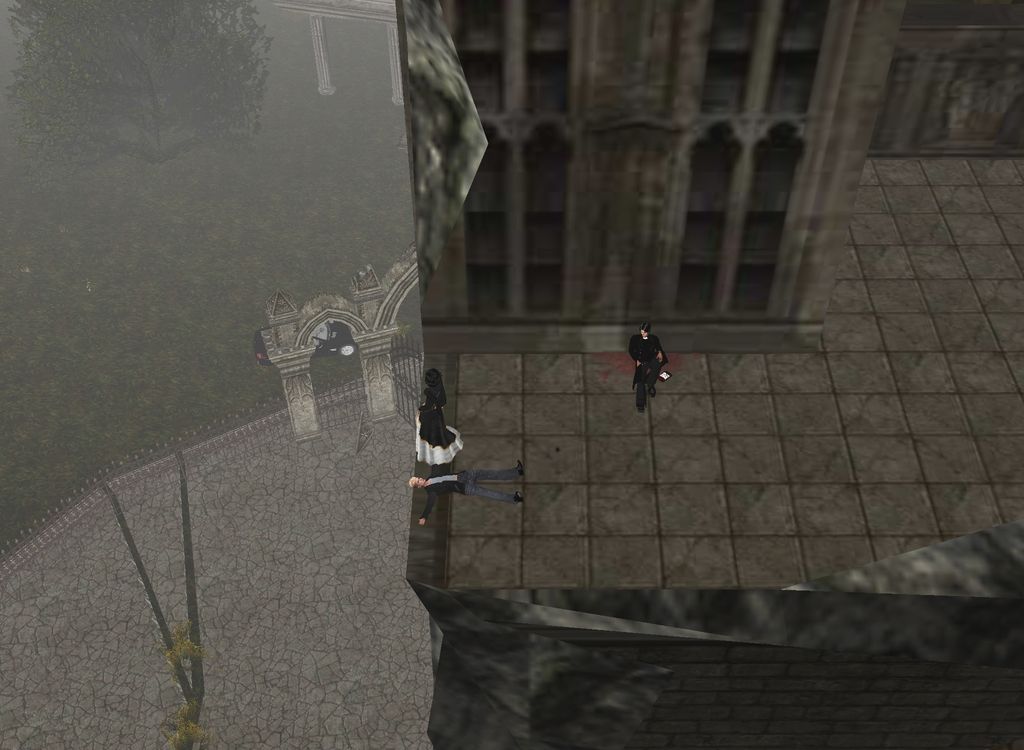

High, aloft, she stands. The very essence of an old world aristocracy. Precariously poised on the edge of the precipice atop the monolithic cathedral, which had long ago been abandoned to fear and neglect, Erzsébet Báthory watches as the black Lexus comes to a halt. From her vantage she has languidly watched the automobile’s gradual progress, along what was once a roadway but was little more than a path, overgrown with the invasion of swaying saw grass and wild shrubbery. For St. Eustace island was avoided not only by the residents of Collinsport, but by the inquisitive throngs of seasonal sight-seers— for there was seldom, if ever, an encouraging word to support such an excursion. There certainly weren’t any picturesque, tri-fold brochures advertising the ancient structure, nor, recounting the history of it’s construction. Even more importantly there was little mention anywhere of the unusual land bridge, which normally would have aroused such curiosity among the tourists, in that the bridge, or causeway, appeared and disappeared with the lowering of the tide, in order to form a connection between the mainland and the island. For not only the Collins Family, but the town council as well had long ago proclaimed the isle to be a restricted area, owing to St. Eustace’s dark reputation. Of course, rather intrepid sight-seers, having gotten word of the natural wonder at the end of Bridge Road, on occasion slipped past the No Trespassing signs, as they trembling in the sea breeze, and so ventured out beyond the rusting gate erected to bar admittance, as does the sea – except, during the aforementioned hours, in which the tide retreats to create a natural causeway – a land bridge of hard-packed sand and smooth washed pebbles, amid an extraordinary array of large, sea-worn, oddly shaped rocks, allowing access not only by foot, but, the courageous automobiles driven by more intrepid drivers.

Whether he was intrepid behind the wheel of an automobile – Erzsébet Báthory did not know. Nor did she care. She had little use for the conveyance. But, she was well aware that if he was of a mind, he would soon be master of whatever he found to be of importance if not a necessity.

Her lips curl in a wicked smile.

Against an autumn sunset of Monet violets and gold, she stands amid the cathedral’s twin, lofty towers (one of which had nearly given way to the years of neglect and the accumulated abuse of severe winter weather—a portion of it having already toppled to the earth below) as she lifts her chin to embrace the headwind. But for all its bluster against the stone façade of the chapel, it would appear the wind, whipping up from the sea, fears to do no more than to lightly feather strands of her hair or gently ripple the material of the golden hem of her dress, which just skims above the roughhewn stone.

With the narrow toes of her soft, black leather boots resting far too dangerously upon the brittle edge of the limestone, the Countess watches Edward Hutchinson, or Count Petofi as he is feared, open the door of the Lexus and step out. Her wicked smile curls: forever fastidious. She observes now as he buttons his jacket and arranges the cuffs of his shirt to the precise ¼ inch he prefers, before he astutely turns to minutely survey the abandoned grounds of the chapel built for no Christian god. Yes, as ever cautious as he was fastidious – well, save for that time in Kor. And he needs to be. For this island conceals a dark power – she can feel it, has vaguely felt it from the moment she set foot upon this accursed isle. But now she can feel the malignant emanation. Reaching out. Attracted by the presence of Hutchinson? Possibly. For whatever had been called up here had never been properly put down.

And rightly the island had been long abandoned. Shunned. St. Eustace’s Cathedral, the monument for which the isle had been renamed, left to ruin. Founded by the right Honourable Reverend Braithwaite Lowery in 1806. He had arrived from Amsterdam by way of a very hurried flight, sometime around midnight, from his Brichester parish – owing to the growing suspicions about odd lights and strange odours said to have been escaping from the cellar of his vicarage, as well as some of the most prurient and unpleasant rumours concerning the fates of several missing girls, along with vague hints of his connections to dubious men and suspected necromancers throughout the Severn Valley – and so with thread-bare pockets, a worn bible, and a smooth toffee voice, he had soon began to gather contributions less from a developing congregation than from the philanthropic families of Collinsport and the near-by environs of Bedford and Logansport.

It was a Collins – was it not always a Collins . . . only—rather than being one suspected of some scandalous or horrendous connexion, this time a Collins was guilty, of all things, heroics. Harriet Collins, the wife of Daniel Collins, the mother of the infamous Quentin Collins, the 1st, while investigating the disappearance of a most favoured maid, (whom she had at first sensibly suspected of having been clandestinely involved in some servants quarter tawdry relation with her husband, particularly, owing to his uncommonly flustered pronouncements concerning his thoughts about just where the missing Isabel might given flight) discovered the Reverend’s unholy rituals. Rites he had brought across the seas to St. Eustace’s island. In her unrelenting determination to force Daniel into a confession of his suspected salacious copulation, Harriet’s continued investigation uncovered, for her, a most unlikely culprit. The Reverend Lowery. And so, invested with information from a livery boy and bearing only a kitchen knife, Harriet ventured out to the St. Eustace’s Cathedral, under the cover of night, to discover a hapless young girl bound to an alter. As well as the right Honourable Reverend Braithwaite Lowery, lost in the throes of some grotesquely guttural incantation, grasping, double-handed, the obscene hilt of an obsidian knife, which he held posed to stab the unfortunate girl between the exposure of her breasts. There in the cathedral, which Daniel’s contributions had helped to erect, she extracted her fatal retribution upon the smooth, toffee-voice villain. A rather detailed account of which the Countess had read during a curious perusal of the Relics of the Anti-Saints she had earlier procured for Hutchinson.

Absently, Erzsébet tosses a hard plastic bag of blood she had been weighing in her right palm so that it falls perfectly onto the lap of the Reverend Trask, who sits weakly propped up against the sturdier of the twin towers. He lifts his head sluggishly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle in his throat sore from the penetration of her fangs. His fingers numbly feel the reassurance of the all too flimsy container for such a precious liquid – the dark contents of which he will later infuse himself, in order to replenish what she has taken . . . his arms scarred now like a junkie’s to placate her desire for blood that is warm.

“This grows wearisome,” She says, her back turned to him, as she watches Edward move around the front of his Lexus. “His mind—it is blocked by a power which even I cannot seem to circumnavigate”

“A power greater that yours?” Trask’s voice rasps, perhaps more sardonic than he had intended. His tingling fingers trying to lift the life restoring blood, only to feel it slip from his grasp, to fall heavily at his side. He sighs in exasperation even as he inadvertently cuts a quick and wary glance over to the Countess . . . and the blonde man, lying near the golden hem of her long, white linen dress. He bears similar wounds on his throat.

“You would do well, Reverend not to allow my gift to exceed your grasp.” She admonishes him.

Trask lifts his head in order to look at her.

He was still amazed. For truly she was now the Countess of all the legends he has ever heard . . . from the moment she had first appeared to saunter down the aisle of his church, he had been struck by her seductive allure, but now—now, she was seemingly restored to the woman, so many of whom had suspected she could have only bathed in the blood of virgins so as to retain not only her remarkable youth and beauty but such an unblemished complexion.

Yes, this was more than just vampiric regeneration. This was transformation. But how?

Some black magic?

Some vile and bloody ritual?

For this was not only in countenance—but seemingly in years.

But good God, how many?

No, not years, but centuries?

The 16th century! It is almost more than can be believed. This woman has lived for more than four hundred years and today she looks even younger than when she had last fed from him . . . which was, what, only a few days before. Upon seeing her, now, he was able to truly comprehend the ravages of the Brides’ revenge which she had borne. For it would appear that years have disappeared from her face. And her damaged hair – which he has watched her all too often involuntarily reach up in order to pull upon stray stands at base of her neck, as if in annoyance of her remembrance of its raven glory – was once more thick and lustrous. Whatever the cause, it was certainly more than being revived by his blood or the hapless man laying at her feet. Of course, he could not help but imagine some horrible, titled room. Cold. Breaths forming in the frosty air. All manner of restraints and dangling chains. A gruesome bath chamber where overhead plated runners and rollers adorned the ceiling, upon which young, nubile women, naked, hung upside down, their hair and arms, dangling, limp, swaying, like so much pornographic meat. Their throats all to be slit. To spurt a crimson rain down upon the languid Countess, so much at her leisure within this her most private of baths, perhaps as she had bathed long ago when she had murdered so many innocent young girls. When they had rightly called her the Hungarian Whore.

“Or, to ever use that term with me.” She suddenly whirls about to look at him, her eyes a-flash with an ire he had seen all too rapidly transform into an elemental wraith.

“Yes, Countess.”

“I leave it to you. But, you will do whatever is necessary . . . you will recover it once more. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“And this time, my good Reverend—you will do well not to allow some foolish schoolgirl to purloin it.”

His reply is silence.

For the Reverend was well aware from her stance that her irritation had grown far beyond mere annoyance and was rapidly approaching the point of vexation and violence. Her mesmerizing and mental prowess, which one would normally associate as but part of the unholy arsenal of demonic powers bestowed upon a vampire were, in reality, quite incomparable to those of the Countess, owing to the amplification of the inherent extra sensory talents she had possessed before her transition. And yet, as formidable as they were, they had not been sufficient to extract the information she desired.

It was not the effects of his blood loss for the Reverend had seen the quick and agile blur of her movements on far too many occasions, as she suddenly turns to reach down and grasp the unconscious Ezra Gregson. Her long, slender fingers wrapping about his throat. Effortlessly, as if picking up a marionette, whose strings have been cut, she lifts him. His feet beginning to flay about, weakly, unable to find solid purchase upon the stone rooftop, as the sudden movement and the painful grip of her fingers, as they wrap about his throat, brings forth some semblance of consciousness.

She can smell the metallic headiness of his blood, oozing between her fingers from the twin punctures, as she raises her free hand in a sweeping flourish in order to suddenly snap her fingers.

She watches Gregson’s eyes begin to flutter, “Can you hear my voice?”

“Y-yes.” Lips slurring.

“Good.” She lifts a finger before his face, “I forewarn you. My patience has all but departed.” Her voice filled not only with a melodic mesmerism but the hint of a barely restrained malevolence. “And so, it would be wise to tell me now what I desire to know. “

The young man, dizzy and light-headed from loss of blood and the constriction of her fingers about this throat, struggles to let the toes of his boots touch the stone rooftop even as her hand, lifting him, refuses to allow them to support his weight. Her fingers are a vice—“I-I . . . I can’t. He won’t—”

But before he could finish once more another pathetic denial of her request, Erzsébet Báthory, pivots her foot, and lifting him further upward from the rooftop, tosses him high into the air, and for a moment, it seems as if he is held suspended at the zenith of his arch from the rooftop, out over the uneven flagstones below, before he begins his descent. Arms and legs flaying, he falls toward the cracked stones, which seem now to be hurling upwards toward him.

Bones are broken and forced through internal organs.

The skull bursts in a hideous wetness.

Edward Hutchinson, approaching the gate of the ornate ironwork fence which encircled the immediate grounds of the cathedral ruins, pauses for a moment, his hand upon the latch, as he immediately recognizes the all too distinctive resonance of a falling body and a head exploding.

The latch is stiff, in need of oiling. As does the gate. It’s hinges creak in protest as he opens it, and are just as objectionable as he closes it behind him and rather leisurely makes his way over toward the crumpled body of the blonde man lying before him.

Rather nonchalantly Hutchinson approaches to observe the awkward positioning of the body, the expanding pools of blood. He takes a careful step back now from the slow, serpentine streams of crimson, running down the slight incline of several of the flagstones, so the flow of blood does not reach the sole of his shoe.

With a stern lift of his brow he looks up to see Erzsébet Báthory atop the cathedral. He lifts his right hand, which holds the old, golden buckram bound book, The Relic of the Anti-Saints, which she had earlier procured for him, and motions toward the chapel, “I shall meet you inside,” he calls up to her.

He looks once more at her bloody handiwork, and turns away from the body to make his way toward the front of the chapel.

Other than offering a prayer much too late, and no doubt unanswerable, from a God that had certainly abandoned him, the Reverend Trask assured himself there had been nothing he could have done to prevent the unfortunate and yet inevitable demise of young Ezra Gregson. He lethargically watches now as the Countess takes a step out over the precipice from which only moments before she had so remorselessly rag-doll tossed the doomed Gregson, aware that as she does so, she will lizard-like descend the chapel wall to the broken flagstones below.

His eyes involuntarily stare at the blood upon the rooftop where Gregson had lain. A darkening stain upon the quarried limestone – which Abigail Brewster, back in 1806, had donated quite a considerable sum, in order to substitute the more durable material for the cheap brick of the chapel’s original design. He strongly suspects the rain, and later, winter’s ice and snow, will fail to completely wipe the stain away. Should he survive, years from now, he is certain, if he were to ascend to this rooftop he will find the dreadful spot has remained.

Morbidly he can not help but wonder just how much blood was there left in him? She had dank her fill – and yet, the flagstones below, will they not be bespattered? His fingers reach now for the security of the blood bag. Drawn for him. To replenish what she has taken. Yes, the blood is the life. For her. And, for him? Not so much. For him it is now death and ashes. There can be no atonement. He fears now even the blood of the lamb cannot wash his sins away.

Suddenly, in his peripheral vision, he catches the fleeting sight of the Countess as she steps out over the edge of the chapel roof – and for a moment she seems to defy the laws of gravity . . . before she is gone.

The dead travel fast.

Yes.

That is more than certain.

As certain as he is damned.

What had she said in Stoker’s novel: unclean.

Yes. Unclean. He was now forever unclean.

But why shouldn’t he be?

Heavily he sighs and rests his weary head back upon the rough, stone wall of the chapel tower as he feels now the full weight of his complicity in Gregson’s death. Feels the full weight of the Trask curse. How odd, murder and sin are what those in Collinsport have always long whispered about the Collins’ – whereas he has full knowledge now that there is a long line of sex and sin and murder tracing back through his own iniquitous descendants . . . all the way back to the renown Reverend Ezekiel Trask, his most legendary forbearer from Salem. Whom he knows now to have been a odious, wicked zealot and a willful deceiver who, being infinitely more amoral than the malicious witch-finders Matigan & Wiley, had persecuted and condemned throughout New England many an innocent young girl to hang or burn for the practice of witchcraft. Called by God, he proclaimed, to be the fierce and wrathful instrument against the unrighteous, which at best, if he believed, was a self-delusion in order to deny the gratification he found to his perverse and sadistic desires. The stripping of young girls to search for their Witch’s Mark. The inducements they offered him not to find them.

And so, at long last, it would seem, the inherent curse, perhaps inevitable, having been named after Ezekiel’s son, had finally found him too hiding in a clerical collar – sired as he was by a linage of religious fanaticism, persecution, perversion, and corruption.

And so, propped against the tower of a church built for a necromantic heretic, Lamar Trask ponders the weight of the bag of blood in his palm as he wondered how he had ever thought he could have escaped the heredity of sin and the insanity of his family. Had his own father not been institutionalized for hearing voices and seeking out teenage girls in order to exorcise the demonic succubi which he believed to be inhabiting them.

Did he not have his own demons?

Even before the appearance of a vampire Countess.

Had he not been drawn into the family curse by the “accidental” discovery of the secret journals of Gregory Trask – written by a hand ever more cramped for space, as if the page itself was seemingly too small to contain the amassed detail of all the vile and explicated history of his infamous ancestors A recondite history of scoundrels and hypocrites, charlatans and thieves, sadists and rapists, and murders too. How oddly paralleling the abstruse history of the Collins’. And there was that word again: odd. Odd. Odd that he should have uncover Gregory’s journals so shortly before she had thrown open the doors of his church and he had fallen to the temptation of her lips; into the damnation of her fangs.

Odd that only that afternoon he been reading the mesmerizing journal’s tale of the trial of Quentin Collins, the 2nd, for witchcraft in 1840. Which in and of itself seemed incredulous. Witch trails in 1840? But then, there was even further incredulity, the discovery of his namesake, Lamar Trask’s involvement in the prosecution; his complicity in falsifying evidence; his more than apparent culpability in the murder of Mordecai Grimes, upon whose land the Gregson’s now oddly resided; his eventual concealment of the disembodied head of a most abominable warlock and wizard, who had been in full possession of Quentin Collins’ supposed best friend, Gerard Stiles. And what a true confidence man he had been, rather than the jovial high-seas adventurer, he portrayed himself to be. In fact Stiles was not even his name. He was in fact Ivan Miller – a man with an infamous past, as the journal so indicated, wanted for embezzlement in France, gun-gunning and smuggling in North Africa, suspected of murder in Portugal, with known accomplices within occult circles. A man who at first had merely set his eyes set upon obtaining a sizeable portion, if not all, of the Collins fortune, before being side-tracked by a vengeful sorcerer’s possession. Overcome by the disembodied head of Judah Zackary: the aforementioned wizard, with a vitriolic score to settle. One he had nearly brought about with the successful execution of the hapless Quentin Collins—were not the truth of his devious stratagem being revealed at the last moment by a Valerie Collins. Publically displaying the head and exposing Stiles as a pawn possessed by the warlock. In he resulting confusion the possessed Stiles was shot, fatally, breaking the spell. And as he expired, seeking forgiveness from his old friend, it was believed by all there assembled that the dreadful artifact had been finally destroyed.

Only, as the journal had revealed, Lamar, who, having not been one to follow the call of the clerical collar, being the upright and well-respected mortician in Collinsport not only collected the body of the unfortunate Gerard Stiles, but had also, discovered that the head of Judah Zachery had not been destroyed. Aware of it’s vast occult powers, he secreted it away, (or was so directed by the head itself) only hours before his own unfortunate disappearance.

And so, as he sat propped against the limestone tower, contemplating the bag of blood, weighing in his palm, he could not help by wonder if it was mere fate, or was it in truth the curse, which had drawn her to his church?

And once she had ravaged his mind – unlocked all his secrets – her interest was more than piqued by the revelations of the Trask’s long concealed involvement with the dreadful artifact . . . the secret family heirloom . . . she had immediately commanded him to intensify his efforts to find the grotesque artifact. Even as she commanded him to keep watch on his friend David, as well as the other members of the Collinsport Ghost Society, and her daughter Nicole. She had forced him to become a unwilling accomplice to her tricks and stratagems, as Elizabeth Bennett would say; collaborating in her plots with him– always with him, whose ashes he had meticulously gathered together for her to perform some unholy ritual in order to bring about his sure and certain resurrection. The Count Andreas Petofi. Whom she calls Edward Hutchinson – a wizard and notorious necromancer from her past. Both of whom were ever more insistent he find the disembodied head. A quest in which he had ultimately been successful, locating the foul object in the abandoned attic of an old carriage house once frequented by Flora Collins, back in the nineteenth century – to only have it stolen away . . . by a school girl!

The far too lovely-to-be-but-sixteen-and-irresistibly-nubile Kimberly St.-Simone. A would be Nancy Drew, who, in investigating the death of one of her friends from St. Andrew’s School for Girls, had inadvertently discovered his clandestine second-floor apartment in the old Brewster Building. Only, it would seemed wherever that horrid head sought to rest, it would find none – and so, his frantic inquiry into precisely who had stolen it, eventually lead him to the lovely schoolgirl – only to find that it had been yet stolen again from St.-Simone. Subsequent inquiry by the Countless, only too aware of the significance of the growing number of decapitations of hapless Collinsport tourists, brought to attention Ezra Gregson, one of the two janitors employed by the St. Andrews School for Girls.

Of course the Countess could have proceeded with a nocturnal visitation of Gregson herself – but she had rather sternly informed the Reverend, owing to his carelessness, the onus was upon him to bring her the head, Gregson, or both.

Now whether or not Gregson’s motivations were solely his own or were entirely directed by the disembodied head of Judah Zachery, Trask had no way of knowing. But what he was more than well aware of was that it supposed to be God who judged the wicked and condemn the quick and the dead. Not some 16th century vampire. And yet, for all his feeling of complicity, in the Countess’s irritated toss of Gregson from atop the chapel, Lamar Trask well knew that Gregson was in point of cat a murder . . . and, while awaiting inside the janitorial office at St. Andrew’s with the weight of the Spurless 206 .38 hanging heavy in his left jacket pocket, searching for the disembodied head, he had found instead the surreptitiously taken images of naked or half-clad schoolgirls via some network of hidden photographic devices Gregson had furtively installed in dorm rooms, in bathrooms, in locker rooms, even in the showers . . . slowly sorting through hardcopies of these lurid images the filthy-minded janitor had hoarded away within the same Timberland boot box within which he had a massed an accumulated collection of apparently stolen, or otherwise obtained, bras and panties . . . it was all too evident the man was certainly contemplating even more horrendous crimes to come.

Of course, he had explained to Gregson, as he waved the M206 Spurless in an open invitation to exit the Janitorial office, he was merely taking the perverse box of his pornographic mementos as evidence.

Blood bag in hand, Trask says in complacency. For all of his brooding and guilty sense of complicity – lifting now to inspect the bag of blood to be certain it was his blood type – he found himself somewhat assuaged by the thought that Gregson’s collection awaited him in the trunk of his Mercedes.

Below, once more walking the earth, Erzsébet Báthory saunters slowly past the ruins of a toppled turret of the church as she approaches the body twisted upon the broken and uneven flagstones.

There is a scent of fresh blood upon the breeze.

For a moment she looks down at Evan Gregson, suddenly struck with the remembrance of a strikingly, beautiful young woman, a handmaid, who too had fallen to her death, her blood splattered upon the cobblestones below, owing to her obstinacy in refusing to admit her misplaced loyalty in an another. There were no others. She was Countess Báthory, and there was but one reward for determined intransigence. She lifted the hem of her white, linen dress and glides past Gregson’s broken body and makes her way toward the front of the abandoned chapel.

The doors stand open. Left so in the wake of Edward Hutchinson’s entrance.

The precise impact of her high, soft, black leather boot heel fails to echo in the vastness of the abandoned sanctuary of the chapel as she slowly strides through the threshold. In fact, there is absolutely no audible evidence of her entry. There is a flutter of birds uncertain as to whether they should take flight or huddle down into the refuge of their nest cradled in the niche of the widening disintegration of a decorative column. The chapel’s neglected sanctuary has given way to a systematic invasion of the twin chisels of weather and the years, working their way upon ill set walls, which have cracked and crumbled so as to allow the light of day, or as now, the diminishing light, to enter, along with various incursions of rude weeds and the slow breech of the creeping tentacles of ivy.

With an aristocratic insouciance she approaches the first of the worn, wooden pews, as the fingers of her right hand leisurely slide over the top of the pew, to fall away, before they absently slap up against the top of the pew ahead, as she watches him sitting unconcerned, his head slightly bowed – her lips curl into a smile: a prayer?

Never.

He is reading.

As always ever with a book. Just as he was when she had first met him at Niepołomice Castle, sitting alone in a niche with a candle and some slender volume. His appearance then of course was the handsome young Englishman with the presumption to stare whenever she was near, not as he was today, within the body of Victor Finn-Gibbon – owing of course to that foolish quest. Where was it? Looking once more for Kor, but not – it was in the Sudan? Yes, with Kitchener

He had been introduced as a member of John Dee’s retinue.

The English mage had come ostensibly to pay his respects to her uncle, Stephen Báthory, King Of Poland (not withstanding Dee’s known association with Lasky, the schemer) – to demonstrate his alchemical prowess . . . although, it was more than keenly obvious he was in search of some material patronage. She and Ferenc were but invitees to court (her Uncle already aware of her growing interests in matters of the occult) in order to see this famous Englishman – and so, not privy to their private consultations, she had still instantly perceived that Stephen saw little value in the English alchemist. In truth his interest should have lain with Edward Kelly . . . and even more so with their over-looked apprentice.

An apprentice? But to whom . . .

“Transcribing for Master Dee or Kelly?” She asked closing the narrow door of the oddly angled room he had been given amidst the set-aside rooms reserved for the servants of visiting dignitaries. The room was very dimly lit by a lone candle, which sat nearest his writing. It gave off a distinctive smoky taper.

“Countess.” He replied with some surprise, sitting back in his chair, as he lay down the pen he had just dipped in ink.

Her observant eyes swept the room as she gave him one of her very best deceptive smiles. She approached the table and picked up one of the pages scanning the Latin, not alchemy, but something older: “An apprentice I am told.” She dropped the paper, her eyes holding his: “But to whom? Neither Dee nor Kelly, that much I surmise.“ She lifts a hand with a slightly waving gesture, “Perhaps, it is Walsingham? Elizabeth’s intelligencer. “

He watched her in mute admiration.

“Tell me Mister Hutchinson are you a spy?”

“A spy?” He leaned back into the light of the candle, its flickering flame giving his countenance an almost most conspiratorial cast as it played odd shadows across his face. That and the sly smile upon his lips, “Countess, I am but a humble student of the magus.”

“Humble?” She lifted a brow and began to move about the room, studying him more than the spare furnishings, the unmade bed. Books on the floor. Quite a collection for an apprentice. She lifted a flounce of bed linen and smelt of it. And already making himself familiar with the maids. Yes, he was as full of himself as he was of deception. She could sense it. For all his Spartan surroundings there was certainly more of the aristocrat than the apprentice within him. Which is why she had made her way furtively to his bedchamber, for being the wealthiest woman in Hungry and Poland, she was more than well aware soon there would be cabals and conspiracies against her. Too many men owed her more that they could pay. And some day, looking at the brash Englishman, such a man as he bay be a valuable resource.

Only, she suddenly sensed something more ominous than a mere intelligencer about him as she stood near the bed. His eyes keenly watching her. She dropped the bed linen upon the floor. “I think you are many things, Mister Hutchinson, but humble is certainly not one of them. Brash and ambitious, yes.” She stepped back to the small table and into the brighter illumination of the candle, “Something, whomever holds your leash, would have detected long before they sent you into this duplicitous morass of intrigue and politics. But, be forewarned, It would be unwise to heed the machinations of Olbrachi Laski.”

“Madam, my interests lie far beyond the realm of politics.” Of course, he had lied. For later she would discover it had all been as she had deduced: he had been secreted within Dee’s entourage by Walsignham in order to follow up on leads given by Phillip Sidney. . . only, set free in Central Europe, he wasn’t working for Walsignman or the Queen. He had a mission of his own.

She picked up one of the books from the table, Bacon’s Demonica. “Here you will find much war and very little alchemy. Even less its infant science. And I can assure you—sir, no one communes with angels.”

“Perhaps they whisper to the devil.”

She gave him a sharp look: “It is dangerous, even in jest, Mister Hutchinson to speak of such things. Particularly, when your Dr. Dee treads closer to magic than to mathematics. Rome has many spies, and not all of them are among the Hapsburgs.”

“I care not for the school of Rome, Madam. You see, I seek another school entirely?”

She lifted a brow. “The Scholomance?”

“You are aware of it?”

“There are rumors. Tales of a lake hidden from the untrained eye.”

“You know of this lake?”

“No.” She told him.

“Perhaps then the Countess knows a Baron Ferenczy.”

“That is another name one should speak of lightly.”

It was thus that their long alliance began with such a simple request. A brief letter of introduction. A letter which not only introduced Hutchinson to the mysterious Baron, whose estate was secured from intervention, be it from ever invading hordes or Vatican spies, lying as it did in the rugged mountains east of Rakus, but, even more so by the whispered rumors and fear of it’s inhabitant. A letter which more than introducing Hutchinson introduced her as well. For soon there were various emissaries from Transylvania appearing at Csetje. Sorcerers and witches – witches whispering seductively of eternal youth and of the Haunter of the Dark, whom the Baron worshiped. Yes, a simple letter of introduction – it would eventually lead to the destruction of her reputation and the dissolution of her lands and fortune.

How it grieved her to see the ruins of her beloved Csetje.

“How many times now have you read that over?” She asks.

“My dear, it is an amazing collection of annotations and corrections. Each time I peruse it, there is yet another revelation,” he replies as he closes the book and places it on the pew beside him like some evil hymnal. “It would appear I badly underestimated Professor Timothy Stokes. I find his occult analysis to be really quite insightful.”

“It is a shame she saw fit to dispose of him.” Erzsébet says as she languidly steps before him and then settles, no, more glides into the pew beside him.

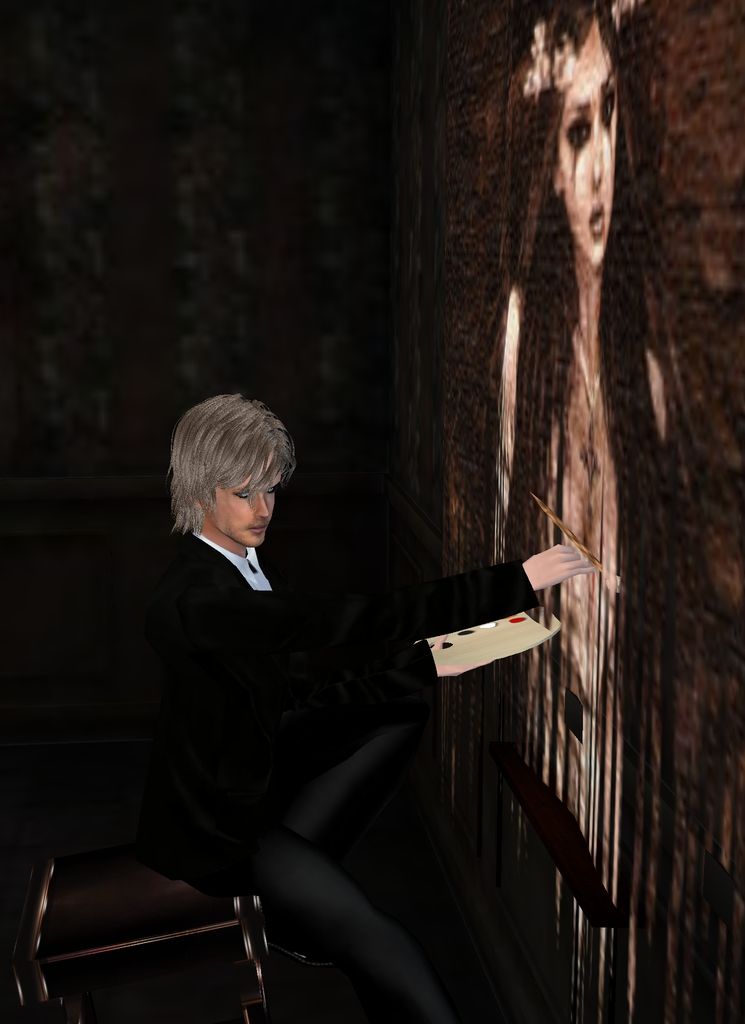

“Quite.” He looks at her unable to conceal his astonished admiration. For there sitting across from him was the Erzsébet Báthory he had first met 1585. “I must say, even blind Charles has not lost his mastery with the brush.“

It had been in compensation for her recent recovery of the Relics of the Anti-Saints, from Dean Corso, whom he had originally hired to purloin the volume in the first place – a plan which had become far more Byzantine than he had ever intended, which of course, he blamed entirely upon Aristede for misunderstanding his directives; but then again, he had been under the enthralling effects of that damned jaundiced, two-act play – and thus, his need for her unique abilities in order to retrieve it. She had requested the talents of infamous Charles Delaware Tate. Although, getting the book back from Corso certainly was not as much an effort, or a considerable use of her network of resources as it was upon his, in order to find the remarkable artist. Particularly one long reported dead.

When last he had seen him, during the commissioning of the painting of Erzsébet they had used to lure the Brides, Tate had been a sad old man –having abandoned his brush and canvas for some rather frivolous artistic endeavours with marionettes – drunkenly lamenting his lack of critical acclaim, quite unlike Phillip George Saltonstall, (Charles tossing a copy of the Providence Journal at him), who was being recognized with a showing at the Rhode Island School of Design. “From which museum walls would my paintings have hung had I never met the great Count Petofi?” he had scowled. The loft littered with empty bottles of Old Overcoat Dry Whiskey, well lain in, lying wherever they had been let to fall. “You have one advantage over Saltonstall,” he had replied, his gloved hand idly fanning apart some sketches lying upon the table between them, “His paintings may hang on a wall, but he is dead. Where as you, my friend, are thrice lived. Tell me dear Charles, how is it that I find you like Jesus arisen from your grave?” To which the drunken painter grinned sardonically, “A secret, Count. One of my own.” Of course he had to laugh at him: “I must heartily congratulate you my boy on whatever sorcery, and to whoever the sorcerer is, but, if you remember, it was I who discovered you and assured you would not be consigned to being anything more than some third-rate hack with a brush. Now, had I been there when you expired, I would have not only resurrected you, I would have restored you physically as well – what are you now Charles, well over 140? I must say life . . . and death . . . you do not seem to have worn them well.” Tate narrowed a brow and extended a tremulous hand, “Then you best ask for whatever you want while I can still hold a brush.” Thus, the painting for the subterfuge of the Brides. And so, later, hearing the sad report of the fire, which consumed not only invaluable sketches and paintings, but poor Charles himself, he had assumed the day had finally arrived in which Charles had descended into the bottle of his despair owing to his enduing and yet unrequited love for his Amanda.

But then, when Erzsébet had asked for him specifically – he surmised that either the report of his death had been yet another a ruse of Charles’, or, once again the mystic artist had found a way to cheat death. For there was no doubt, Charles had died once before. He had gone back to Collinsport, disguised as a poor landscape artist Harrison Monroe, in a futile attempt to reunite with his lovely Amanda – and there was never any doubt as to her loveliness, for Charles had created her whole cloth from his imagination. But, he found her in love with another, and so Charles decided to die in the arms of the personification of his love – the woman he had created from mere charcoal and paper. But then, several years later he had found him in that Providence loft, resurrected, frail and forlorn having abandoned his brushes to play with marionettes. And so, he had reached out into the occult underground to seek once again his gifted protégé.

“It is most fortunate that the report of his death was once again far too premature.”

“Indeed.” He said softly, “But alas not without its consequences. Whatever method used left him blind and disfigured. And whomever . . . . But what is life without its mysteries? One I will certainly solved. Did I tell you, I eventually found him living on the northern coast of Scotland.”

“Scotland?”

“Ever the recluse.”

“Taking away his scars you could have restored his sight.”

Hutchinson nods thoughtfully, “True – but what would be the lesson in that?”

And for a moment Erzsébet remembered the harlot maid. The honey and the ants. “Nevertheless . . . his gift is truly amazing. One which you should better regard in the future, Edward.”

Never one for churches, he grows tired of the uncomfortable pew, “It was rather a significant undertaking in order to locate him, so my dear, do hold on to him.”

“I have given him a suite of rooms in the Aspinwall Hotel. The concierge has been given instructions to assure he is kept . . . comfortable.” She places her hands in her lap, “While I find Amanda Harris.”

He smiles sardonic, “You have decided to play cupid?”

“I mean to secure an asset – I am not as reticent as you when it comes to matters of the heart. I shall assure she reciprocates his affection.”

“Ever the romantic.” He adjusts his right cuff, “Now, as pleasurable as it is to sit here rather uncomfortably and reminisce about our poor Charles, surely Erzsébet, other than to observe your handiwork with the hapless Mr. Gregson – whom, I must assume did not give up the location of the ever elusive head of Judah Zackary ?“

“No – Zachary’s spell was more powerful than I had expected.”

“Yes, well, Judah was always a bit more than anyone . . . expected. But (and he lifts his gloved hand, to point with added emphasis) it is imperative that the head be located –“

“Trask will recover what he has lost.”

He gives her a frown, “The Trask’s have never been known for their guile or for their successes. However that maybe – I will leave it to you Erzsébet. And so . . . as I was saying, why have you asked me to meet you here. ”

She sits back and with a mischievous gleam in her eye and with a luxurious flourish of her hand, she draws his attention across the ruined chapel toward what appears what he had assumed upon entry to be some renovation begun in the ancient sanctuary. In particular, she motions toward a paint splattered scaffolding with it’s array of scattered carpenter’s tools, odds-and-ends of discarded cuttings from 2×4’s and 4×8’s, paint cans, brushes, and a mismatched array of tarpaulins, upon which lies a light powering of sawdust – all abandoned about some much larger tarpaulin draped about whatever the object of their endeavours.

“Renovations?”

“As I recall, Edward, you made a request of me.”

He turns in the pew to look better observe the construction. “The Rose Window?” he asks quizziczlly.

“Behold Edward,” she replies regally, “Once again, I grant you your wish.”

He rises to look at the strategically obscuring brown canvas, “My dear Countess, you forever astound me.”

Her lips curl into a satisfied smile, “I found it in Philadelphia. It had to transported and installed— I chose a place secured by its legends.”

He arises from the pew and steps across the sanctuary, grit and debris crunching under foot. The Countess follows. Together they move past the old stone altar of the long abandoned chapel, “You were correct, Edward. It would appear Edward Crane did in fact build a house in Kingsport – although, it no longer stands. It seems parts of the old architecture were dismantled and sold off – I think they call it repurposed.”

She moves over to the large tarpaulin and grasping it with her left hand, in a magician’s like flourish, whips the canvas down and tosses it away to reveal the section of a wall which appears to have been removed from some other structure and reassembled to stand here in the old chapel.

A partial wall containing the intricately designed “Rose Window.”

Hutchinson steps forward to inspect it. His gloved hand’s touch is more a caress: “Magnificent, is it not.”

“What is for Edward?”

“Their return.”

“Their return?” And she cuts him a sharp glance. “And pray what was your plan had I not found the window?”

“As always, I depend upon ingenuity. If not my own – then theirs. They are not without their own allies.”

“Yes.” Her tone grows darker. Her blue eyes narrow. “We have known each other for centuries, Edward. “ Her sharpness of her canine teeth quite incisive as she speaks. “But, I swear . . . If this goes all wrong – as it all so clearly did in Paris . . . . We are done!”

“As no less than I would expect, my dear.” He nods. “We were ill prepared in Paris, and that can not happen again. There is too much at stake. And so, it is best we make haste to draw upon our own dreadful allies.”

And he smiles his infamous smile.

End Scene Cue Music